It all started back in 2015 with a challenge on the image hosting service, Flickr. The challenge was to post 5 images over 5 days in Black and White (B+W) The images had to be your own, and could be converted from colour or shot in B+W. Then the album of your images would be collected together so we could all see each other’s contributions. I’ve still got my album here – and the cover photo of the wind turbine across the howe/valley from our village was one of those images.

The point of the challenge was to inspire more of us to appreciate B+W and hopefully to incorporate B+W into your photographic work. Well, it acted as a powerful trigger for me. I’ve worked in B+W ever since! I’ve collected books on the masters of B+W and studied their ideas and actual photos, and I am still sometimes surprised at how much I love black and white images.

When we have millions of pixels, and an almost inexhaustible range of tones and tints from our digital cameras and computers, why hark back to the plain B+W world? But like many photographers, I have found there is still so much wonder to be found in these seemingly ‘simple’ images. So I went in search of more information, and the opinions and experiences of other more experienced photographers. And I was surprised to discover just how alive and vibrant the B+W world is in the 21st century! And I am hooked! There is so much subtlety and beauty in B+W photography, it can be as powerful and subtle as the Japanese Sumi-e brush painting

The only photography magazine I subscribe to is “Black+White Photography” I’m not a magazine reader – it is the only magazine I read – so B+W really is important! In an interview for B+W Magazine in 2015 photographer Bruce Percy summed it up perfectly for me:

“For a long time I really struggled with black & white because I think it’s a lot harder to do well than colour is. I think a lot of beginners push up the contrast and they think it looks really exciting, but you learn as you go along that that kind of image is quite hard to look at for more than a couple of minutes. It becomes quite fatiguing, everything is shouting at you. A really good image doesn’t get tiresome to look at because there’s much more subtlety to it. The person who crafted it is doing it in such a way that they are pulling your eye around.”

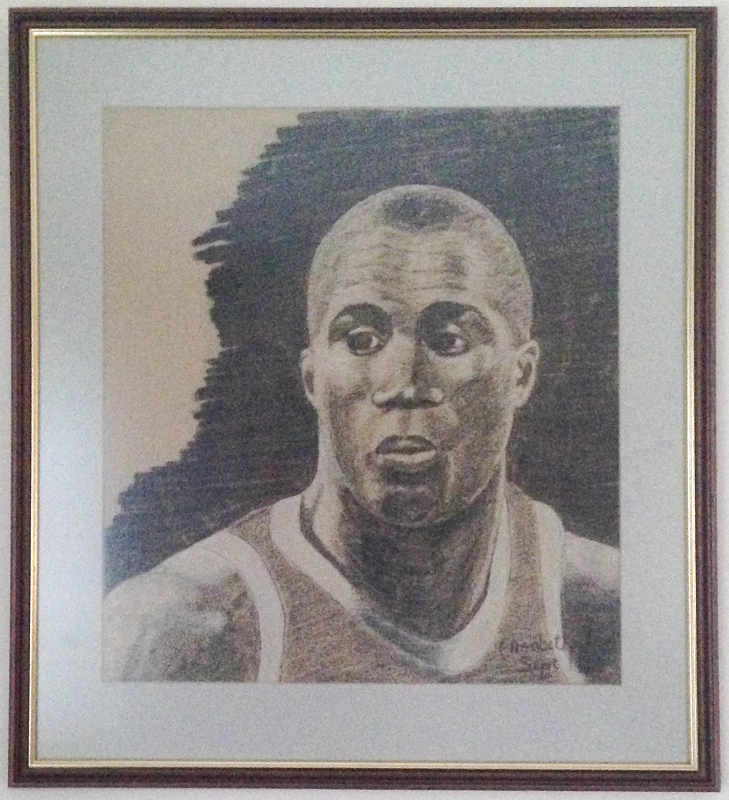

I began to understand what drew me back to B+W time and time again, and how my photography could relate to, and draw from other cultures that I admire, and other artistic strands in my own cultural and personal experience. I draw in charcoal with pastel tints, but I somehow hadn’t made the connection with my photographic work …

Is B+W photography so different? There is a pared down quality, a minimalistic feel, and a simplicity of lines and shapes that is clearer when colour is not a part of the picture.

Here the eye is drawn to the setting sun – it captures the attention b.y the brightness of the colour.

Now what you barely registered before, the light striking the houses and the street is so much clearer. The eye can travel around the image, rather than being caught and held by the sun itself.

So – how to set about developing B+W skills? I don’t want to take the ‘purist’ route and return to rolls of film and shooting on non-digital cameras, and developing my own negatives. I want something easier than that! But like many others, I have wondered whether it is better to shoot in digital B+W or to shoot in full colour and then convert to B+W on the computer.

And I found my answer – well, the answer that suits me best – in “The Photoshop Darkroom” by Harold and Phyllis Davis. (Although published some years ago, in 2010, it is still a book I refer to and return to)

Shoot in colour, and process your shot in full colour too, using a system of several layers to bring out the full tonal potential of the image. Then convert to B+W and again use several layers to adjust the final image.

Sounds complicated, but sometimes it only takes 2 or 3 layers to get the effect you want.

And finally – another shot from the same evening shoot as the previous one taken at Banff in Aberdeenshire, Scotland.

Here the light is lower and less intrusive, but the eye is drawn to the blue light of the sky. But what catches me every time I shoot here is the stark headland.

I did a little crop to the shot to strengthen the composition With a foreground crop and a B+W conversion the dark headland really stands starkly between the sky and the sea. Lightening the sky (in the colour version before conversion) helps to outline the shape of the headland, rather than taking the eye away from it.

I’m always experimenting, and finding new ways to use the power of B+W. I use Infrared cameras, and I also seek out photographers whose work in B+W speaks to me. One such is Michael Kenna. I have his book “Forms of Japan”. You can get lost in those images ;o)

I’ve got another, more recent article ‘Lose the Colour’ here and one about converting from colour to B+W here

Flickr holds Elisa’s online Photo Gallery

© 2018 Elisa Liddell