Introductory Comments

Although I want to discuss Sassoon’s war poetry, I propose to begin by looking at some diary entries in his Journal for 26 June 1916-12 August 1916, held at Cambridge University.

It is a given that any discussion of someone else’s literary work – including this one – is an interpretation inevitably shaped by factors (conscious and unconscious) on the part of the reader that have nothing to do with the words (stories, novels, poems, plays) as they were written by the writer. And given also that diary entries are – for the most part – essentially a conversation with oneself, it seems to me that they provide an opportunity for the prospective commentator to find a guiding perspective for approaching the task of reading someone else’s work.

Happily, Cambridge University has undertaken to make Sassoon’s Journals available online via their Digital Library; and the people who have carried out the hours of work necessary to achieve that are deserving of our thanks and gratitude.

The Journal in question can be found here where its physical condition is described as follows:

The volume is a ruled notebook and mostly comprises diary entries. It shows some signs of damp damage to the fore edge of the text block and there is mud in the grooves around the inside cover where the end papers overlap the covering on the boards. There are some ink bleeds at the edges of the pages. This damage and mud may be from the trenches.

This information is important because it emphasises that the contents were contemporary immediate responses to what was happening around him. They should not be read, therefore, as prose equivalent to Wordsworth’s ideal vision of poetry as ‘emotion recollected in tranquility (sic).’ – which was one of the early (and continuing) criticisms of Sassoon’s war poetry, that it does not display appropriate poetic ‘distance’, that it is not so much poetry as satire or epigram.

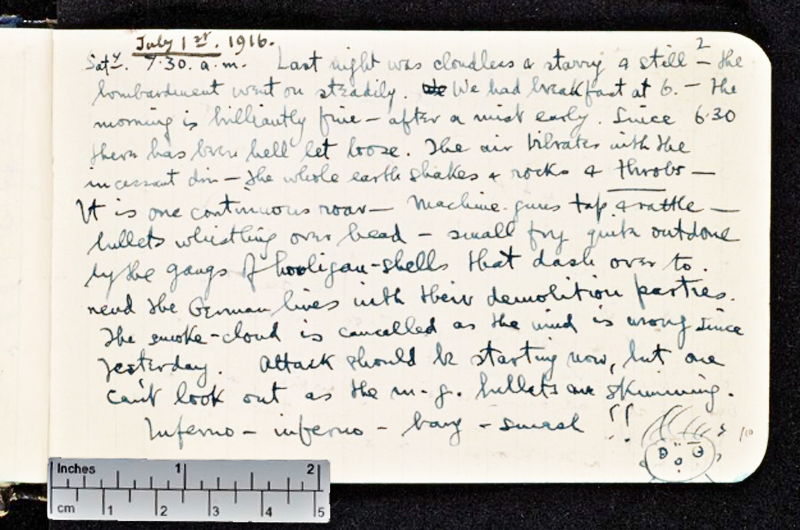

The first entry I want to look at is for July 1st, 1916 – a date significant as the opening day of the Battle of the Somme, when the British Army suffered its largest ever casualties in one day of 57,470 men, 19,240 of whom were killed. Sassoon (who did not take part in the assault at the time) writes as an interested observer:

July 1st.1916

Saty. 7.30. a.m. Last night was cloudless & starry & still – the bombardment went on steadily. We We had breakfast at 6. – the morning is brilliantly fine – after a mist early. Since 6.30 there has been hell let loose. The air vibrates with the incessant din – the whole earth shakes & rocks & throbs – It is one continuous roar – machine-guns tap & rattle – bullets whistling overhead – small fry quite outdone by the gangs of hooligan-shells that dash over to rend the German lines with their demolition parties. The smoke-cloud is cancelled as the wind is wrong since yesterday. Attack should be starting now, but one can’t look out as the m.g. bullets are skimming.

Inferno – inferno – bang – smash !!

Despite the overpowering sense of noise and disorientation it is fascinating to see how controlled Sassoon’s handwriting is on the page, irrespective of the almost shorthand ‘feel’ of the punctuation, the sudden double exclamation marks and the final doodle of the startled face at the bottom right-hand corner:

Also noticeable is the inclusion in this factual narrative of ‘hell let loose’ (emphasised by the repeated ‘Inferno – inferno’ at the end) the phrase ‘gangs of hooligan-shells’, as if some more ‘poetic’ image irresistibly forces its way into the forefront of Sassoon’s mind. His very conscious use of language – which is a constant in even his shortest poems – is evident here as he seeks the words that best paint the scene and his emotional reaction to it. This might almost stand as a general description of his poetic struggle to find a language that works irrespective of whether or not it conforms to accepted ideas of ‘poetry’.

The second entry I want to present was written three days later, on July 4th, when Sassoon’s battalion was fighting at Mametz Wood. The literary reference to Inferno in the first entry changes to the brute reality of the dead bodies now appearing everywhere:

July 4th. 4.30 a.m. The Battn started at 9.15 am &, after messing about for over 4 hours, got going with tools, wire etc & went through Mametz, up a long communcn trench with 3 very badly mangled corpses in it. Came down across the open hillside looking across to Memetz Wood & out the end of Bright Alley. Found that the Irish were being bombed & m-g’d by Boches in the wood & had 15 wounded. A still gray morning; red east; everyone very tired – A man, short, plump, with turned up moustaches, lying face downward & half sideways with one arm flung up as if defending his head & a bullet through his forehead – a doll-like figure. Another huddled (?) & mangled, twisted & scorched with many days’ dark growth on his face & teeth clenched & grinning lips.

12.30 p.m. These dead are terrible & undignified carcases – stiff & contorted. There were 30 of our own laid in two ranks by the Memetz-Carney(?)road – some side by side on their backs with bloody clotted fingers mingled as if they were handshaking in the companionship of death.. And the stench – indefinable ..- And rags & shreds of blood stained cloth – bloody boots(?) riddled & torn.

It is, perhaps, worth repeating that these descriptions are contemporaneous accounts of what Sassoon and everyone else had to deal with. They are immediate, unmediated by any consideration of the possible effects on the sensibilities of readers and critics; and it is clear that such images and experiences cannot help but be seared into his memory, inevitably to emerge in his poetry – and then to be criticised as evidence that (as per Edmund Gosse) Sassoon didn’t always think correctly or record his impressions “with proper circumspection”.

[Perhaps the clearest example of this is Sassoon’s poem Counter-Attack, published in 1918 but written a year earlier. The first stanza opens with an apparent parody of military reportage – except for the second and third lines which are classic pathetic fallacy – emphasising the professional competence of the British Army:

We’d gained our first objective hours before

While dawn broke like a face with blinking eyes, Pallid, unshaven and thirsty, blind with smoke.

Things seemed all right at first. We held their line,

With bombers posted, Lewis guns well placed,

And clink of shovels deepening the shallow trench.

It is easy to see how such a description would appeal to his contemporary readership, how this might satisfy the hunger for details as to what fathers or brothers or sons were enduring. Established poetic convention would then expect him to introduce ideas of more universal interest or significance, to widen the appeal and significance beyond families worried for their loved ones by touching on some general sympathies in the manner of, say, Wilfred Owen’s Anthem for Doomed Youth. Instead, Sassoon offers another vision:

The place was rotten with dead; green clumsy legs

High-booted, sprawled and grovelled along the saps

And trunks, face downward, in the sucking mud,

Wallowed like trodden sand-bags loosely filled;

And naked sodden buttocks, mats of hair,

Bulged, clotted heads slept in the plastering slime.

It is not surprising that such lines appalled readers like Gosse and prompted them to accuse Sassoon of a perverse impulse to sicken and dismay with graphic brutality. It seems as if he revels in the dismemberment so flatly but vividly described in a surfeit of fragmentation of disparate limbs so anonymous that this nightmare world denies any coherent individual identity either for the dead or the living.]

However, it seems to me both interesting and significant that Sassoon’s emotional response in his Journal – despite the opening comment of ‘terrible and undignified carcases’ – focuses on the almost peripheral personal details of death: the physical proportion and posture of the man with turned up moustaches registered before the briefest afterthought of the bullet through his forehead; or the accidental touching of hands in the ranks of the soldiers laid out by the roadside which prompt the resonant comparison with a handshake of greeting between companions. It is as if he tries to restore some sense of dignity, of human value, to the unknown corpses he encounters which might to some degree counter-balance the accusation of perversity in the opening stanza of Counter-Attack, where he makes plain how the destruction and fragmentation of the bodies otherwise makes them insignificant and less than human.

His instinctive expression seems clearly suffused with poetic sensibility embedded in and supported by a strong sense of empathy set against the pervasive indefinable miasma of decomposition. I want to suggest from the outset, then, that all the negative comments about Sassoon’s supposed sensationalism and constant attempts to shock readers by going out of his way to describe the physical horrors of war need to be tempered by this sense of his identification with the corpses he comes across and describes. However offensive and upsetting his poetry might seem at times his language choices in these immediate jottings depict an almost invisible fugitive humanity set against the recognition of the overwhelming inhumanity of industrial warfare.

This sense of the personal and the human struggling to maintain some sense of itself comes alive in later entries, where, amidst the military reportage of what is happening around him and who has died or been wounded and what objectives have been taken or not, he writes of important individual events and reflects on what might be if he survives. For example, some ten days after the description of the dead bodies above we find – on July 14th – the following:

The 2nd Battn are bivouacked 300 yds away by the Becordel road. I had a long talk with Robert Graves, whimsical & queer & human as ever. We sat in the darkness, with guns booming along the valley, & dim stars of camp-fires burning all around in the dark countryside, & a gray cloudy sky overhead, and the moon hid. And there I left him with his men sleeping a little way off. Tomorrow they’ll be up in the battle. where things are going well for us. but no definite news has come back yet.

Here he manages to capture a sense of the preciousness of human companionship (this time among the living) set against the eerie backdrop of artillery pieces booming in the darkness, and at the same time creates a memory poignant with the unstated awareness that tomorrow they may all be dead or badly wounded.

And on Sunday 16th July we find another quiet moment of introspection amid the talk and background singing, a sense of a life now lost forever whatever happens:

Sunday. evening. We’ve just had dinner in the tent, where you can see the camouflage paint smears against the light, like birds flying stiffly, & all sorts of queer shapes. It’s a drizzly cool evening & the Battn are still up by Mametz Wood & there’s no fresh news to speak of. And the others are sitting about the tent talking futile stuff – & the servants are singing together rather nicely by their bright shell-box-wood fire outside in the gusty twilight. And I’m thinking of England, & summer evenings after cricket matches & sunset above the tall trees, & village streets in the dusk, and the clatter of a brake driving home. Perhaps I’ve made blob but we’ve won the match; & there’s another match tomorrow – Blue mantles(?) against some cheery public school side, & there’s the usual Nevill Ground wicket & I’ll be in first & old Kelsey & Osmund Scott & all the rest of them. So things went three years ago; & it’s all dead & done with. I’ll never be there again. If I’m lucky and get through alive, there’s another sort of life waiting for me. Travels & adventures & poetry; and anything but the old groove of cricket & hunting, and dreaming in Weirleigh garden. When war ends I’ll be at the X roads; & I know the path to choose. I must go out into the night alone. No fat settling down; the Hanmer engagement idea was a ghastly blunder – & it wouldn’t work at all. That charming girl who writes to me so often would never be happy with me. It was my love for Bobbie that led me to that mistake.

(‘Bobbie’ is Robert Hanmer, brother to Dorothy to whom Sassoon had got engaged earlier in 1916 – presumably to sublimate or displace his affection/sexual attraction for her brother. Sassoon was here just short of his thirtieth birthday and beginning to think of having children – even though he knew he very much preferred men and determined to remain chaste.)

The nostalgia that seems to induce these memories of cricket matches and English summers morphs into an acceptance of how illusory and essentially meaningless ‘the old groove’ was and the almost grim acknowledgement of a future of isolation and even alienation as he sees himself journeying alone through an endless night. This sense of dislocation – even in the company of his fellow officers and men he is alone and lost in thought – also becomes a powerful theme lurking beneath the surface of his war poetry.

To-night I am hungry for music. And still the guns boom; and the battle goes on three miles away. And Robert’s somewhere in it, if he hasn’t been shot already. He wants to travel with me after the war. anywhere – Russia – for preference. And whenever I am with him I want to do wild things, and get right away from the conventional silliness of my old life. Blighty!- what a world of idle nothingness the name stands for; & what a world of familiar delightfulness! O God, when shall I get out of this limbo? For I’m never alone here – never my old self – always acting a part – that of the cheery, reckless sportsman – out for a dip at the Bosches. But the men love me, & that’s one great consolation. And some day perhaps I’ll be alone in a roomful of books again, with a piano glimmering in the corner, & glory in my head, & a new poem in my work-book. Now the rain begins to patter on the tent & the dull thudding of the guns comes from Albert way; and I’ve still got my terrible way to tread before I’m free(?) to sleep with Rupert Brooke & Sorley, & all the nameless poets of the war.

[There is a sense of prophecy in these last few words. Catherine Reilly in her 1981 Scars Upon My Heart, Women’s Poetry and Verse of the First World War came to the conclusion that, if identified by virtue of the fact of being alive at the time and having at least one poem published about the war, then there were some 2225 British ‘war poets’. In 1991 Anne Powell, using a similar definition in her A Deep Cry: A Literary Pilgrimage to the Battlefields and Cemeteries of First World War British Soldier-Poets Killed in Northern France and Flanders, counted some 66 British ‘soldier-poets’ killed on active service on the Western Front. Clearly, what Jon Silkin terms “the dead weight of the evaluating attitude” has squeezed most of this writing to the same dust as the authors themselves.]

Such entries as these do much to reveal Sassoon’s tortured self-doubts hidden behind a public mask of reckless bravado, coupled with a determination that (if he manages to survive) his life must have a greater sense of purpose than the old habits now seen to be ‘idle nothingness’ and ‘familiar delightfulness’ conjured up by the notion of ‘Blighty’ – a determination which he was to excoriate some six months later in his poem ‘Blighters’. Beneath the yearning for escape and solitude lies an awareness of the constant threat of increasing pain, of course, somewhat dampened down perhaps by the careless reference to Graves not being shot already. But Graves was wounded, and on July 21st the news (wrongly) came through that he had died:

And now I’ve heard that Robert died of wounds yesterday, in an attack on High Wood. And I’ve got to go on as if there were nothing wrong. So he and Tommie (Tommy?) are together, and perhaps I’ll join them soon. “O my songs never sung, And my plays to darkness blown” – his own poor words written last summer, & now so cruelly true. And only two days ago I was copying his last poem into my notebook – a poem full of his best qualities of sweetness & sincerity, full of heart-breaking gaiety & hope. So all our travels to ‘the great, greasy Caucasus’ are quelled. And someone called Peter will be as sad as I am. Robert might have been a great poet; he could never have become a dull one. In him I thought I had found a lifelong friend to work with. So I go my way alone again.

There is an ineffable sadness here that amply demonstrates that the quality of sincerity did not belong to Graves alone. The repetition of ‘So’, ‘So’, ‘So’ is suffused with loss and loneliness. If it is the case that much of his war poetry seems to suggest an angry bitterness that sometimes diminishes its other effects, it is clear from this passage that he was all too conscious of the importance of the individual deaths that made up yet became insignificant in the overwhelming slaughter. The final death toll of the 141 days of the Battle of the Somme is estimated at over one million men.

Two days later he felt extremely unwell with a high temperature. It is tempting to think that this was in part a delayed reaction to the (false) news of Graves’ death. The entries I’ve quoted certainly reveal how finely balanced was the impact of the outer experience of the war on his sensibility.

By the following morning he was a patient in the New Zealand hospital at Amiens. Diagnosed with dysentery at first (one of the symptoms of the trench fever he was later assigned) he was expecting to return to active duty but instead was transferred to No. 2 Hospital at Rouen on July 30th where the still-alive Graves was recovering from his wounds, though the two did not know of each other’s presence. Sassoon ended up in Oxford on August 2nd and spent the next six months convalescing in Somerville College, meeting such pacifists as Ottoline Morrell, Bertrand Russell and others and embarking on the journey which was to result in not only some of his most memorable poetry but also the (in)famous A Soldier’s Declaration almost exactly a year later.

I want to suggest, then, that these Journal entries show Sassoon as a complex, troubled and somewhat conflicted and damaged individual. Through a mixture of accidents, illnesses, reassignments and hospitalisations he spent only four months or so of active service in the front-line trenches while serving throughout the war. In that brief time, however, he developed a reputation for fierce if reckless courage, won the Military Cross and was recommended for the Victoria Cross. Further, it seems to me that try as he might to hide the pain of his intelligence, self-awareness and acute sensibility beneath the mask of this outer persona of the reckless sportsman the intensity of his reactions to the dreadful reality around him compelled him to strive to find a new poetic language to describe his experience.

The difficulties of reconciling these qualities resulted in both popular high-profile success and an academic judgement, a received opinion as it were, that was less laudatory, and which has resulted today in his consignment to the status of ‘trench poet’ rather than simply ‘poet’.

It is unsurprising. Poetry, like other attempts to grapple with the world, only becomes art when it transcends the context which created it; if it remains trapped within its boundaries then it is simply another mode of expression. ‘Trench poetry’ finds itself constrained within its context simply because its subject matter is so narrow, however powerful and affective it may be. Further, it is as if the First World War created such a strong gravitational field that the poetry it inspired seldom escaped its overpowering darkness and the distinct interpretive community of readers who shared a common background of fear, loss and bereavement – and who read the poetry exactly as Owen described his own response to Sassoon in a letter to his mother on 15 August 1917: “(and am feeling) at a very high pitch of emotion.”

Equally, of course, the context also created what we might term a distinct creative community of writers who shared the same themes, images, techniques and rhetoric – because just as the First World War can be seen as the first industrial conflict so there is a sense in which its impact and processes shaped what might be seen as an equivalent production line or industrialisation of verse created out of the same raw material – which Middleton Murry for one thought dangerous, in that it might pass current as poetry when all it had was “the element of poetical popularity, for it produces an immediate impression”. This has obvious relevance to Sassoon, of course, as I hope has been demonstrated in the passages quoted from his Journal. And it is certainly a valid comment on many of his shorter poems, which are closely akin to Bruce Bairnsfather’s cartoons of the period in their vivid visual acerbic intensity capturing frozen moments in time. Further, of course, Wilfred Owen famously referred to Sassoon’s “trench life sketches” in the letter to his mother quoted above.

How far that judgement of Sassoon’s work being somewhat less than ‘poetry’ also applies to others of his poems is a question the following discussion attempts to answer by taking another, occasionally longer, look at some of what he actually wrote.

Next section here

© 2019 Mike Liddell